© Credits photo: Thomas Marroni

Though there is a rich history of narrative painting based in fiction, from the ancients to Delacroix, the sources for such work seem to have run dry over the last century. Faced with this situation, Kelsey Shwetz has nonetheless refused to disavow the effects made available by certain configurations of character, incident, mood, etc., choosing instead to turn these components of narrative, gem-like, to see what else their facets might betray, how they might be arranged and imagined in more dynamic relationships with their picturing.

Her method is elegant in its simplicity. For two years now, she has worked almost exclusively on canvases whose content is drawn from a myth of her own creation — I suppose it’s worth noting that she typically refers to it in conversation only as “the fable,” highlighting its aspect of lightly worn moral education and, in turn, the comic delight of its elaborate, inventive forms of punishment. The beats of its narrative are, I suppose, obvious enough, and retrieving them is a pleasure better left to each viewer. Instead, let’s briefly consider the way her paintings deal with this dense, allusive core, in order to illuminate one perspective which makes available the complex embroidery of Pale Slope of the Hour, the artist’s first solo presentation in Europe.

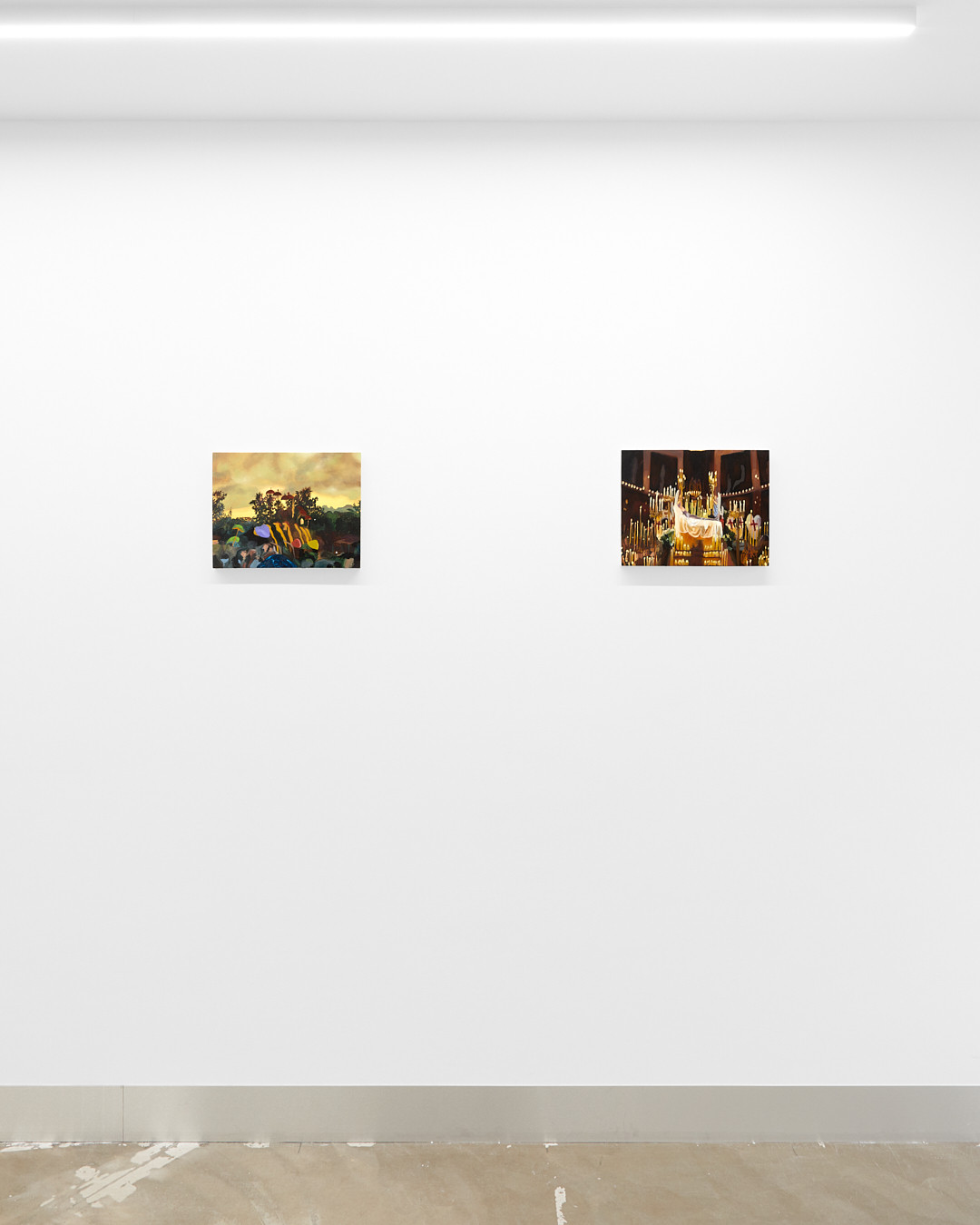

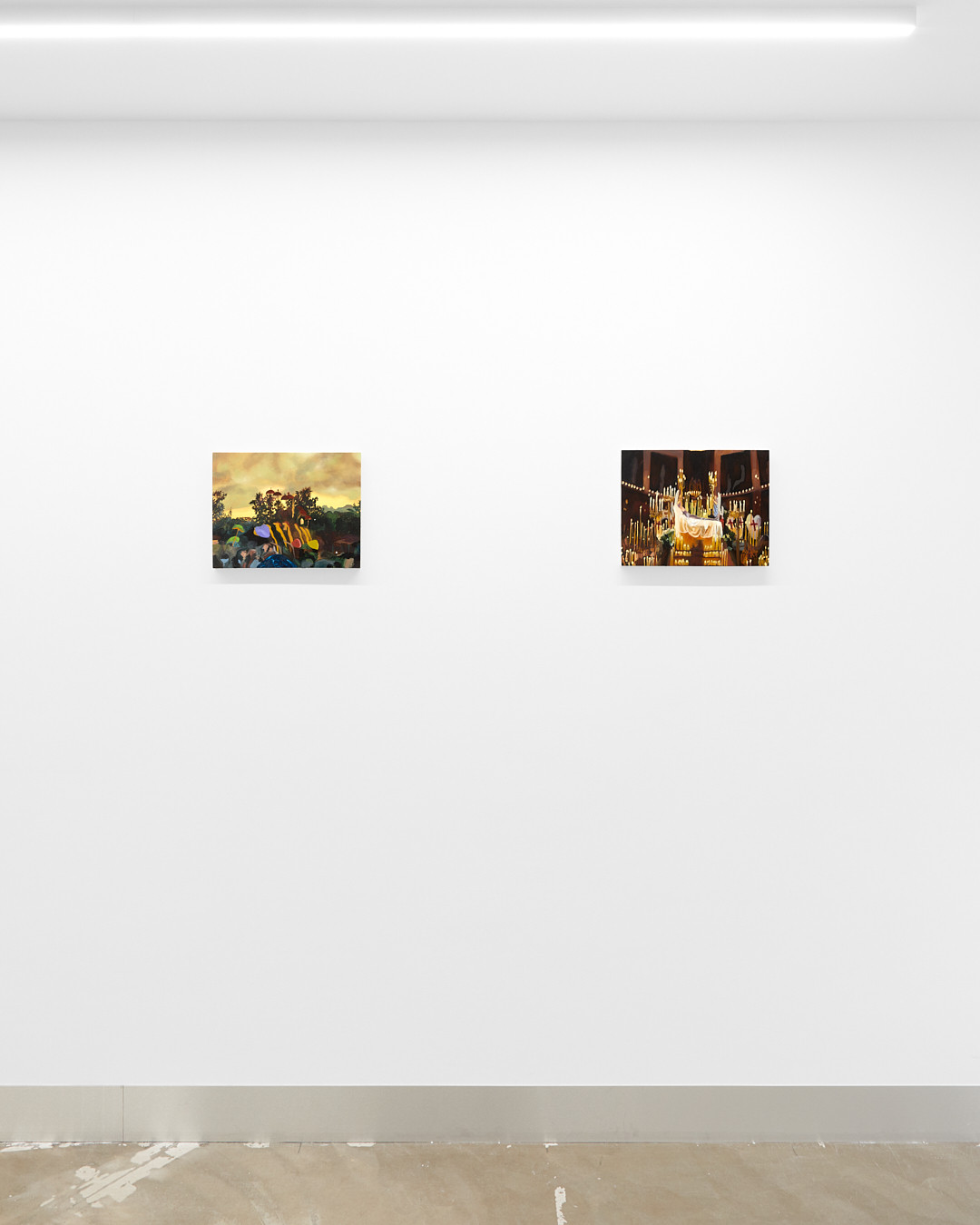

The thirteen works comprising this show can be placed into four general categories: an overture; one complete cycle, or as the artist prefers, “canto,” of the myth (6 paintings); one partial cycle (3); and a group of smaller, interstitial paintings (3). This is of course an inherently unstable ordering. Equally compelling relationships between works from different categories emerge as soon as any order is articulated; even within the complete cycle, the overall effect varies dramatically depending on the order in which one experiences each picture, ranging from deep sorrow to something like the grim happy ending of a fairytale. Still, the steady modulations of both motif and composition — the artist moves back and forth between multiple paintings at once, replacing and adding in a literal cycle which allows for resonances to emerge naturally — continually whisper at connections, subtleties that when seen demand reflection.

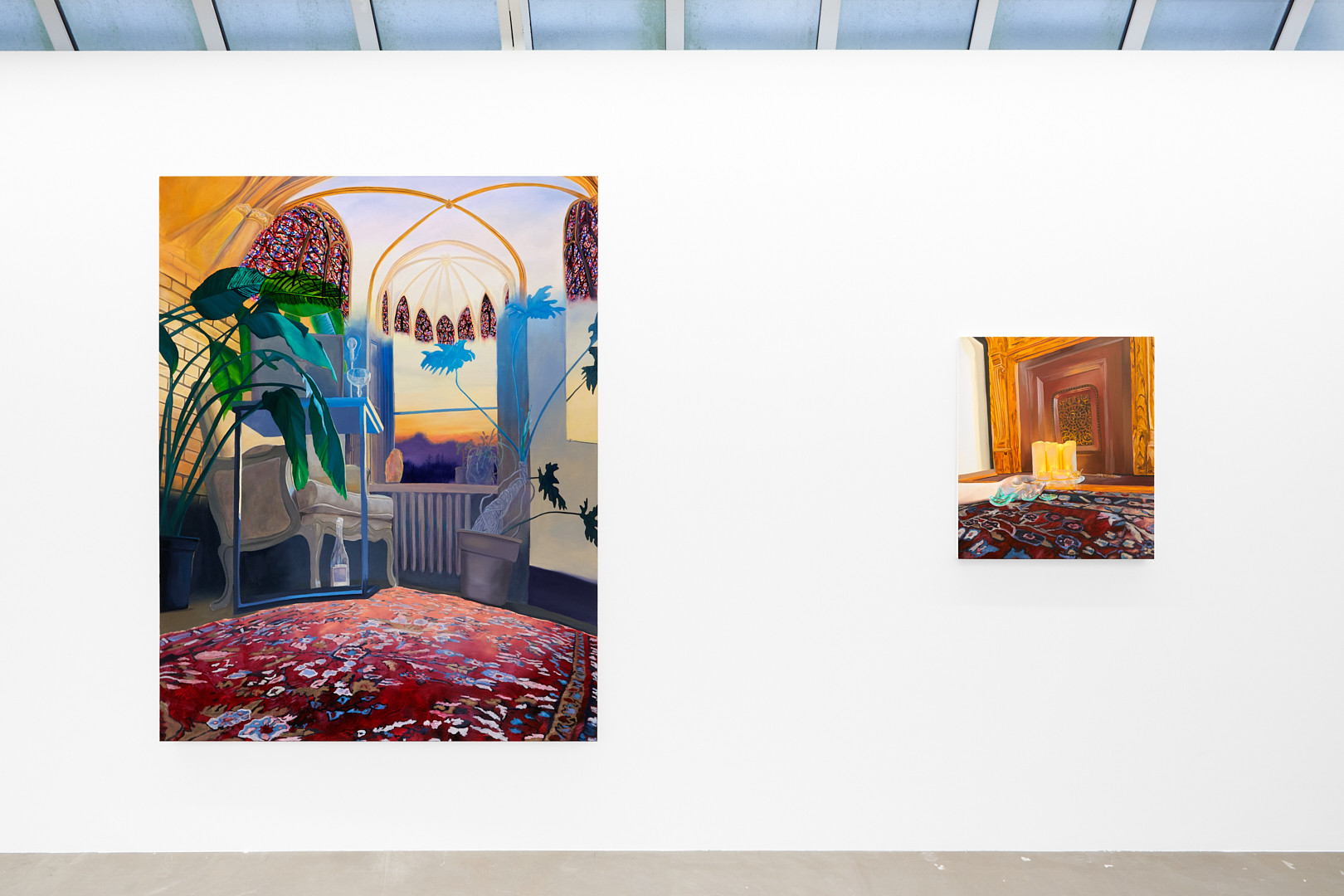

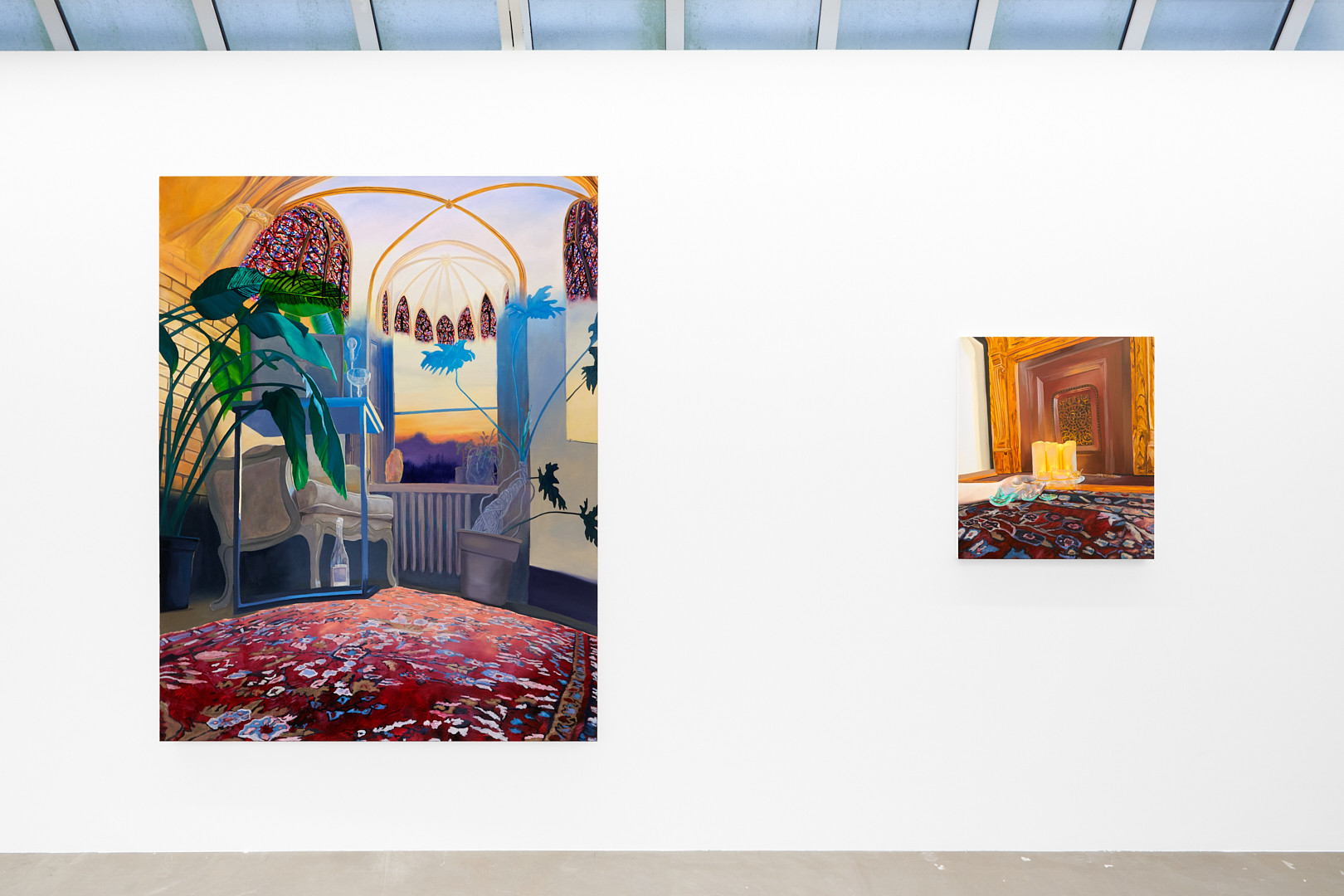

Instability and reflection: these are also key to her compositions here. The overture, Temptation, summarizes the former with appropriate efficiency. At the most basic level, the geometry of the composition, its perspective, is skewed with a sense of deadpan chic. The lines defining rug, floor, wall, and window decline to settle down into calm rectilinear space, preferring a more rhythmically pleasing zig-zag. (Her lively drawing practice continues to factor more heavily in the work.) Atop a cheerful, brushy rug in peach and lemon, a Philodendron Selloum grows from a terracotta pot and continues seamlessly into its place within the composition of a stained glass window showing, it seems, a scene from Eden. This strange transition is made all the stranger by foreshortening which renders the distance between pot and wall both impossible and harmonious, the room somehow enormous and claustrophobic.

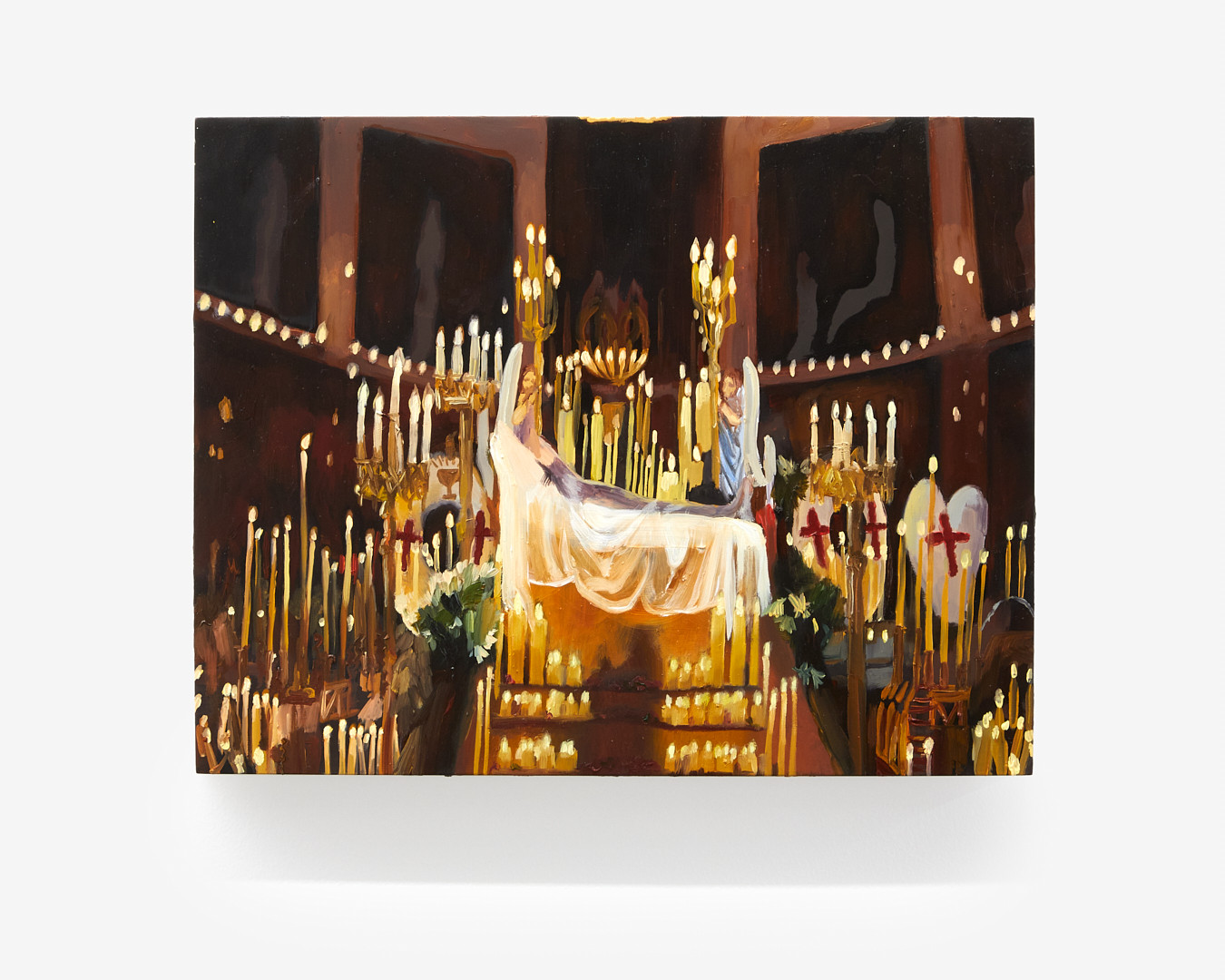

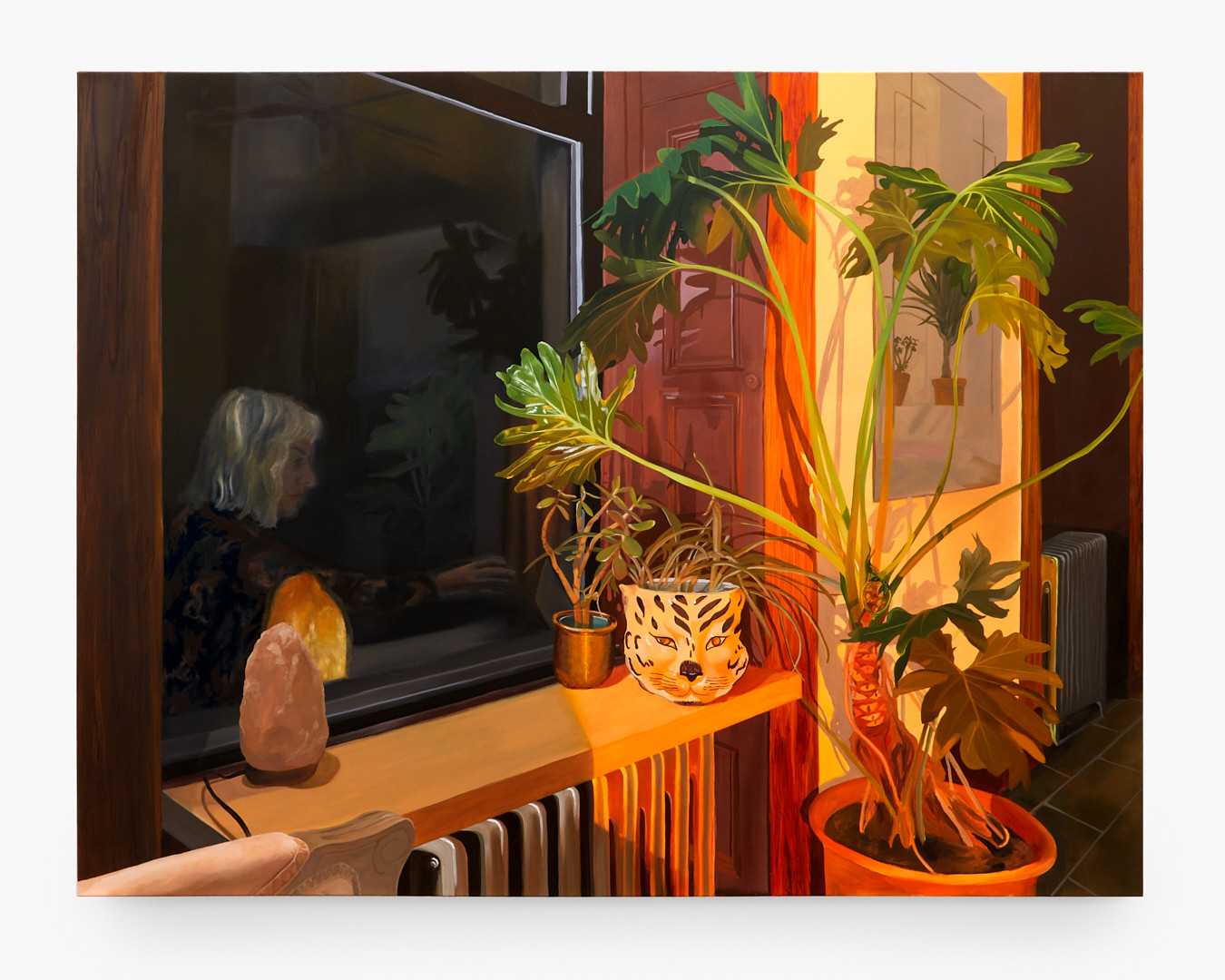

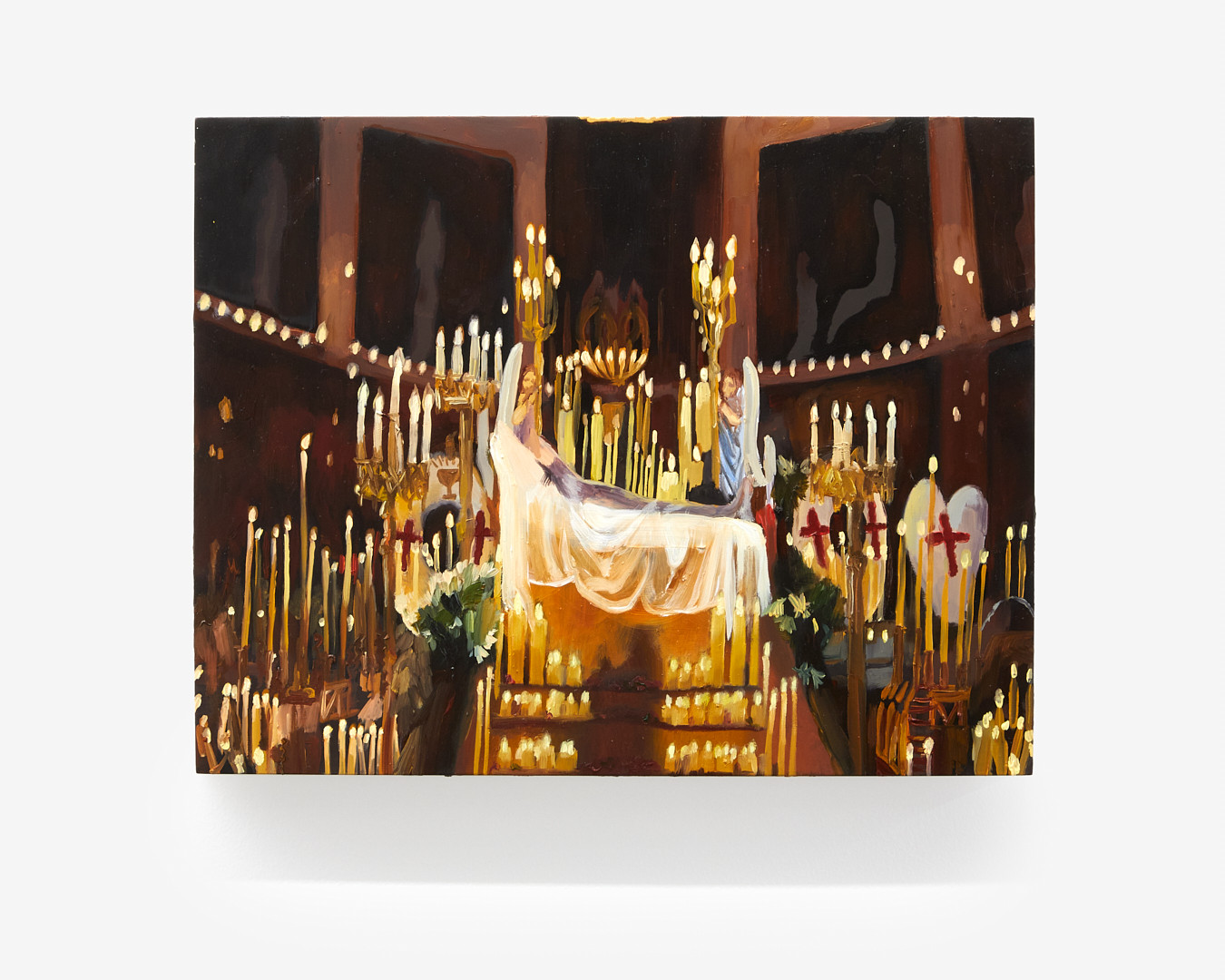

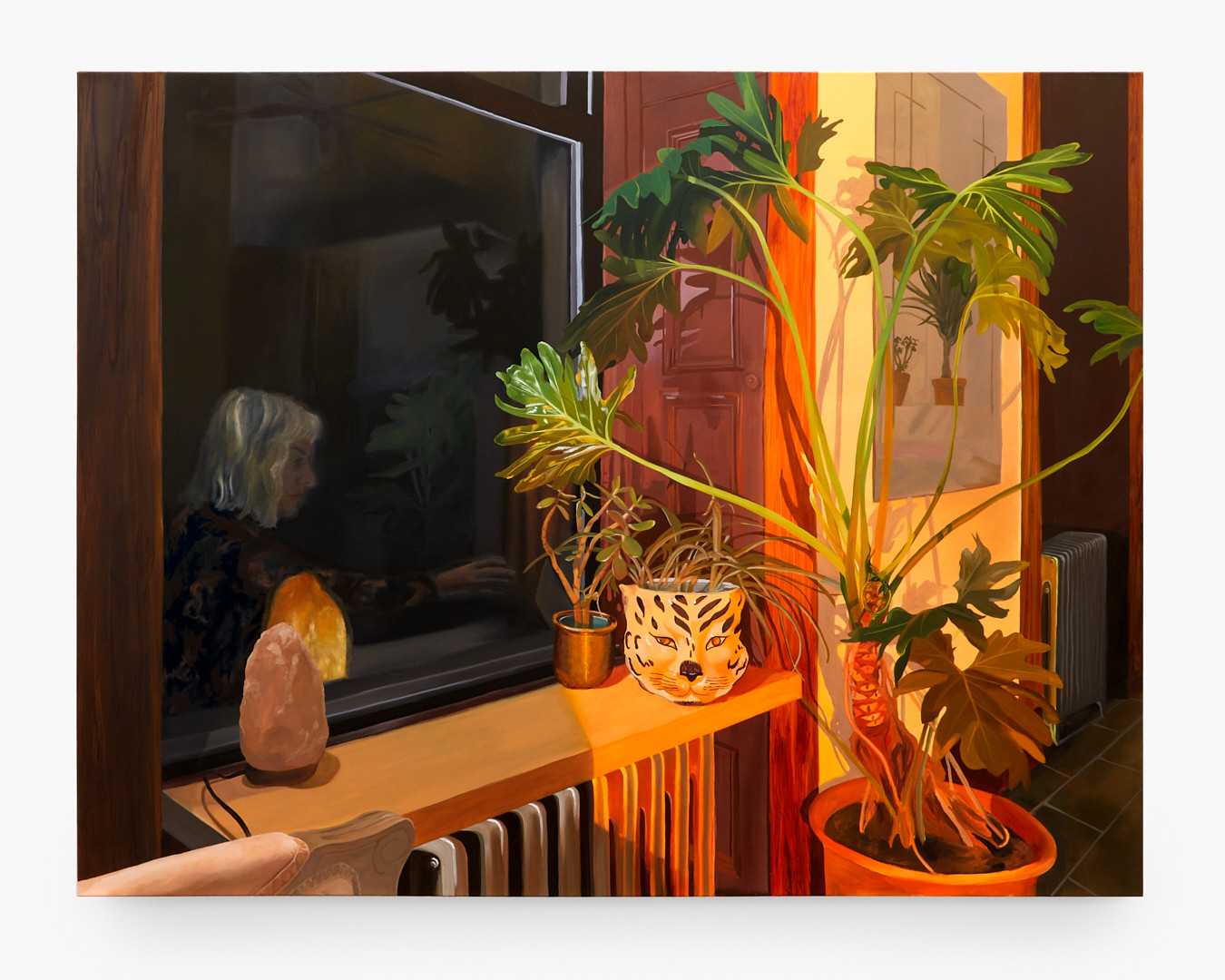

The order of the gallery hang is only one route through these paintings, so we could move from Temptation to any we choose (all, finally, would connect). We might, for example, follow the shape of the stained glass to its compositional equivalent in Night, the window which reflects the artist — though we seem to see this scene from the perspective of someone in her position, she appears to be absent from the present of the painting: a kind of premonition—as she reaches toward what we’ll see, after a bit of looking, is a small glass fruit. This might lead us naturally to the large, cheerful landscape, Fruit to Glass, but it might just as easily turn our attention to Plants to Flesh, where a hazily rendered figure also appears out of darkness on the left edge of the frame. Or we could move to Dawn’s First Light and Revenge, elaborating a fuller picture of the interior in which these paintings occur.

The delight of this work, then, is in following the rhyme of an odd corrugated wall and a sketched in radiator, the slipperiness of windows and mirrors, the journey of a candle or coup glass. Still, for all of its welcome and indulgence, there’s a sense that it might be possible to find just the right perspective, a view from which its layers of story, motif, gesture, and composition would pop into perfect focus. Presumably at least one person has found this position, and now invites us along.

Phil Coldiron